Yeah, I Did Some Vibe Coding Too

This is a story about my recent experience Vibe Coding. The work itself isn't impressive and this writeup isn't different than the many gee-whiz posts you see these days. I didn't do three apps in a day. But I wanted to write up my experience, mostly to give me an excuse to tell an old tyme programming story from the 1900's.

Today, 2026

While I'm on a break I'm taking a Vibe Coding class. It's a fun excuse to play with some new toys, and it's well taught, and I like doing things with my friend Jane.

One interesting tidbit: the first day of class, February 3, 2026, was one year and one day after "vibe coding" itself was coined via tweet. That name seems to have stuck, for the time being at least. On last week's ATP they said that by this time next year this will probably just be called "coding" and I bet they're right.

Anyway our week one assignment was to code up a game. In about two hours and $10 I had a something up and running. I spent another couple of hours futzing with version control, documentation, and hosting. But that's it!

It's pretty basic, and not all that much fun, but you can play it here. It's hosted on Github pages, just like this blog. The code and construction notes are in checked in.

This was my first experience with Replit. It's impressive and fun. This was what was recommended for the class and the good folks at Replit were nice enough to give us all $30 in credits, which I had plenty to spare. Most of my comrades presented apps that were fancier than mind with 3d graphics, sound, and more interactive game play. some also said though that they ended up spending much more than I did, so YMMV on costs.

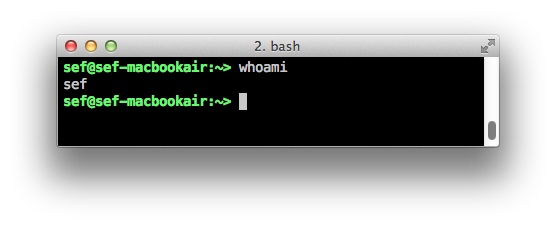

One interesting part was dealing with integration. To get their code deployed onto my personal website site required wiring up a GitHub workflow, which I'd never done before. No problem, Replit took care of that too. Then I asked Gemini to get local hosting running. When I hit a permissions problem and a crash I had to resist the urge to copy paste the error messages into a search boxes and Stack Overflow, like I've done for years. Instead I asked Gemini to debug and sort this out for itself and it did straight away. Pretty great.

Forty Years Ago, 1985

Why'd I pick this weird old chase game? Well, that's the more fun and nostalgic part of the story.

When I was fourteen years old, I spent the summer hand-coding a video game. I'd gone to a family gathering and my older cousin Erik brought his Mac from college. It was the first I'd seen a Mac and fell in love. I thought the Daleks game he had running on it was so cool. The screenshot on the right is from that Classic Mac website of that game that I found online, and is exactly how I remember it looked.

Upon return to Fresno I got to work. I spent most of the rest of that summer writing a clone of Daleks on my Apple //e. All hand-coded 6502 opcodes and twos complement math for branch offsets by hand (I didn't have an assembler), in pencil on graph paper. The hardest part was getting smooth animation working, since the Apple //e "hi res" graphics system was super quirky.

It took about two months to get it working. It's the first time I can remember being in a flow state and I loved it. It was my first "real program" and began my lifelong love of computers.