Friday was my last day building Stanford's open-source online education

platform. What started as a lark turned out to be one of the most

fun and rewarding times in my career. So I'll use this opportunity to

reflect back on the project and what we accomplished.

First a Little History

"MOOCs are just information technology happening to higher education."

-- George Siemens

I joined Stanford in 2012, coming off of my self-imposed sabbatical.

My goal then had been to get hands-on again, to sharpen the technical

tools. I did a few online classes and hobby projects, but my friend Jane

suggested I could do some good and have more fun working in a group back

on the Stanford campus (I'm an alum, after all). So I joined her and a

small group of engineers in a conference room in the fourth floor of

Gates.

Recall what was happening in education in 2012. Stanford's

first three big Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) had

just made big splashes. Later that year the New York Times would famously

declare 2012 to be the Year of the MOOC. What could consumer-grade

web tech could do for higher education? Or even do to higher ed? The

low cost and ease of cloud computing removed many of the barriers to trying

new things out. You approach experimentation completely differently when

things get 100x or 1000x cheaper. Profs were literally getting out their

credit cards and buying Wordpress blogs or throw up virtual machines for

automated grading. Wild stuff.

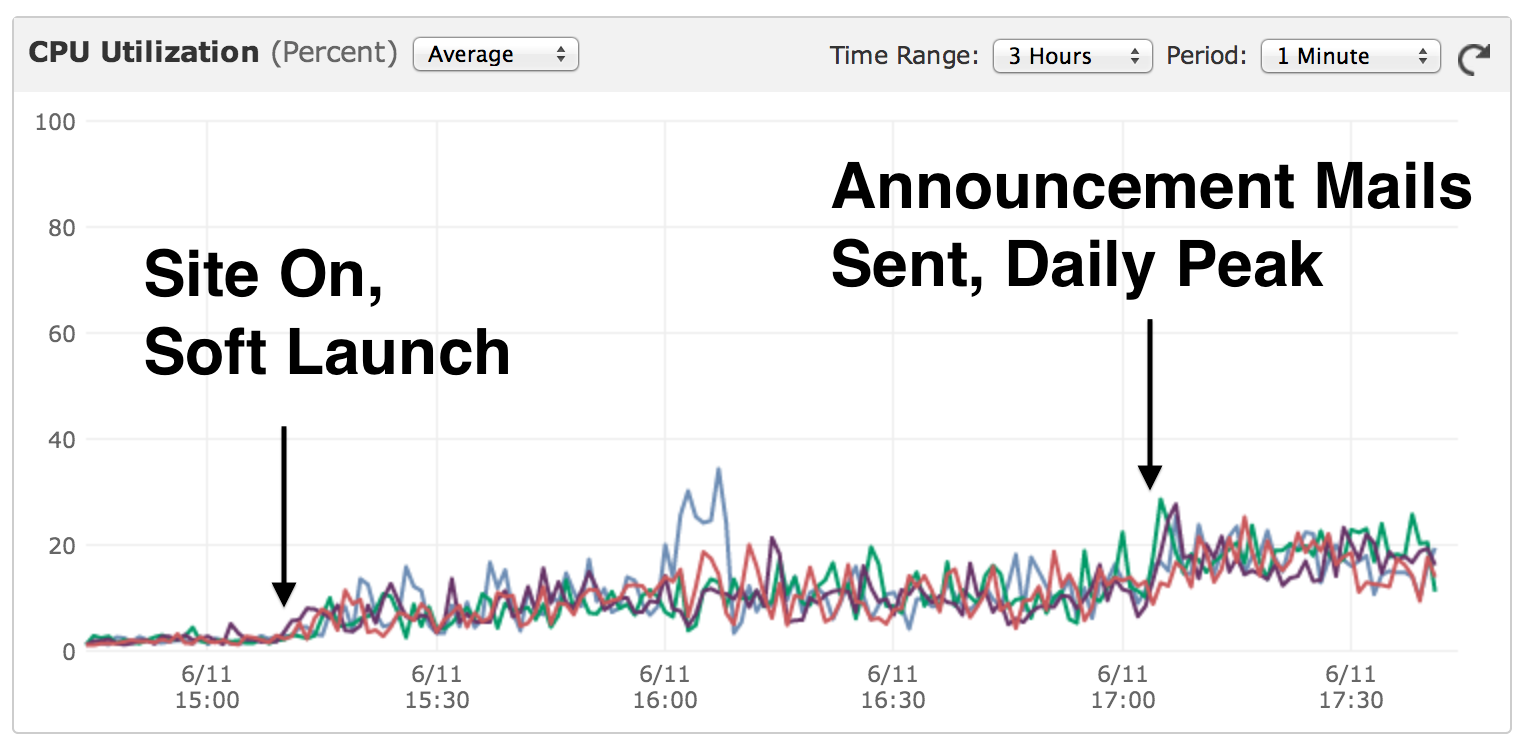

So this was the environment when I joined Stanford. That first summer we

built Class2Go to host free online courses. We went from empty

buffers to a live Python/Django site for hundreds of thousands of enrolled

students in eleven weeks. Man, that was a fun ride.

We built Class2Go for a few reasons. First, we feel strongly that Stanford

needs to control its destiny. There is no "file format" for online ed

content, so every course development online is a bet on a platform. And

we didn't want to be beholden to one platform vendor (still don't). In

2012 the technology that had powered the early MOOCs were becoming "platforms"

and moving off-campus. While we were happy with the success of Udacity,

Coursera, and (a year later later) NovoEd, we were also a bit wary. They were

going to have to repay their investors at some point. The last thing we

wanted was for online education to look like textbook publishing or academic

journals. We know what happened there.

Second, we wanted to have a broad impact. We were lucky enough to have

an engineering team at Stanford, but it makes no sense for every school

to develop their own platforms. This kind of project is tailor made for

open source development, and I've advocated strongly for that since the

beginning. Not only would this mean many others could benefit form the

software, Stanford would benefit from many more developers and see many

more use cases (and we have).

And the third reason is the need to modify the platform. There are many

reasons why you need to get hands dirty in the code. It could be just

developing a point feature, like tracking changes in peer evaluation.

Or it could enable a whole new use case, like authenticating

on-campus students. Our teachers and researchers want to do

interesting work online, not just put up courses. They have great ideas

about using the things that make MOOCs unique (different cultures, scale,

data-gathering, etc.) as powerful tools, not obstacles to overcome. (To

hear more about interesting online ed projects, follow the Stanford VPOL

Signal Blog).

Scaling Up With EdX

Come early 2013 we started seeing some interest from others to use Class2Go

outside Stanford. While exciting, we were concerned about the quality of

the code. There were giant missing features that were going to be hard

to write (e.g. peer evaluation). And the code was quick and dirty,

with nearly zero tests and other things a "real project" needs. We could

have backfilled all of that, but it sounded like a lot of work.

It's around that time that we started talking with edX. Our academic ties

to MIT, Harvard, and other edX consortium members are strong. We liked

their philosophy and approach. And our technologies were similar: both

Python/Django stacks running in Amazon, etc. We decided to work together.

Rob Rubin and I got the deal done quickly, mostly between sessions

at PyCon. In April 2013 we announced that we'd shutter Class2Go

and adopt the Open edX platform.

Stanford didn't join the XConsortium. Rooted in our belief in the power

of open source, we made open-sourcing their platform a condition of us

working together. EdX didn't need convincing. But Stanford was of

a forcing function to do it then, and it did take some work. They pushed

the button on June 1 2013.

For the past year and a half the Stanford team has operated as a virtual

member of the extended edX engineering team. They've been a fun group to

work with, generous with their time and good collaborators. We've been

running the platform successfully now for over a year, supporting dozens

of courses for Stanford students, MOOCs, online high school students, and

many other uses. We've contributed back many features, like theming,

course email, instructor analytics to name a few.

I've spent a lot of my own time helping to make sure the Open edX project

a healthy open source project. It's not enough to just open up the code,

to have a thriving community you have to conduct your development out in

the open. Beyond helping other institutions get up and running I've worked

to drive the open-source agenda overall. With my friend Nate Aune

last May we published recommended changes to technology, governance,

and community. And with Paul-Olivier Dehaye this past June we

hosted the first Open edX workshop, in Zürich. I think those efforts

have made a difference.

Moving On

I've heard the siren's song of the startup. Last Friday August 29th was

my last day at Stanford. I'll post about my next gig when the time

is right.

But I do feel good about moving on. The Stanford engineering team is solid

and productive. The engineers work well with each other and have a good

breadth of skills. The course operations team is dedicated and strong.

Jane Manning will do great running the team in addition to her day

job as of product management -- she's done this before and knows the product

inside and out. And Jason Bau, the Stanford Open edX tech lead,

will continue to anchor eng and ops.

And what about the open source community? I do feel like the flywheel is

starting to spin up. EdX is fostering this in several ways, I'll mention

two. First, they are in the process of opening up their bug tracking

database and sprint planning (Jira). That's a key step to doing true open

development. And second, I'm really excited to see the first full-on

Open edX conference happening this upcoming November. I expect

that to be well attended.

EdX has asked me to continue on as a member of the Technical Advisory

Board, which I am happy and honored to do. I look forward to staying

plugged into the project and working with my friends on the board (Armando,

Ike, Jim, Phil, Ross...)

Thanks to my many friends on the project: the Open edX engineering team,

especially Jason and Jane; the team in the Office of the Vice Provost for

Online Learning, especially Professor John Mitchell who made this

possible; and my many friends at edX. There's a lot to be proud of over

the past two years, and a lot of good work ahead.